A Literary Mystery Solved

—A Research Piece for Scholars—

While there continues to be a welcome variety of approaches to Oscar Wilde’s life, many of the incidents in the Wilde story tend to remain the same.

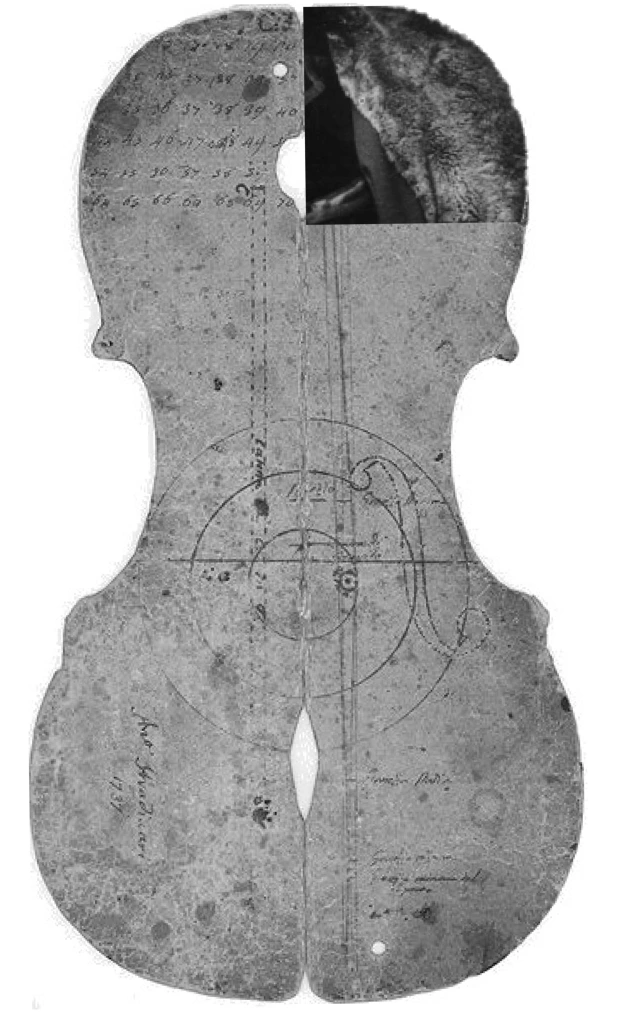

One of the recurring plot points in most studies and biographies of Wilde and his circle, over the last 30 years, is the occasion of the opening night of the Grosvenor Gallery, when Wilde purportedly wore a coat in the shape of a cello.

This intriguing story became the subject of conversation I had at the recent annual dinner of the Oscar Wilde Society in London. Because of my work on Wilde and dress, I was asked by an academician engaged on a related theme whether I knew the earliest reference to Oscar’s cello coat—as current research could only trace the story back to Ellmann (1987).1

I confessed I did not know. So I decided to investigate.

The Grosvenor Gallery

The 1877 inauguration of the Grosvenor Gallery, on Bond Street in London, was a seminal event for Wilde and the Aesthetic Movement, because it provided a home for artists not embraced by the more conservative Royal Academy.

It is perhaps significant that Wilde’s first ever published piece of journalism was a review of the event2; indeed, he wrote a second review two years later when the exhibition became annual.3

This earnestness for the Grosvenor was recognized by those two opera comiques Gilbert and Sullivan, and when they satirized the Aesthetic movement, in Patience (1881), they included a reference easily descriptive of Wilde as a denizen:

A pallid and thin young man,

A haggard and lank young man,

A greenery-yallery, Grosvenor Gallery,

Foot-in-the-grave young man!

Wilde probably never lost his attachment for the place, for in The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), he has his protagonist insist, “You must certainly send [the picture] next year to the Grosvenor. The Academy is too large and too vulgar…The Grosvenor is really the only place.”4

It is reasonable, therefore, to infer that Wilde would have thought the opening of the gallery a special enough occasion for him to wear a special coat. The problem is to find a primary source5 to establish whether he did.

The Cello Case

As we know, Ellmann referenced the cello coat in his 1987 life of Wilde. For the record, this was not Ellmann’s first mention of the story: he had already alluded to it in a lecture (which was later published) that he delivered at the Library of Congress on March 1, 1984.6

However, in the 1987 biography he expands upon it as follows:

Ellmann’s source for the story is identified in a footnote as: “‘Secret Diary of a Lady of Fashion,’ Evening News, 15 Nov 1920.” —i.e. an article of that name in a London newspaper.

The first point to note is that Ellmann is slightly in error about the title of the article. But even Horst Schroeder’s7 correction of the word Secret to Social does not help us find it, because the necessary publication is apparently absent from newspaper archives. The lack of this source is no doubt why current knowledge has foundered at this point.

So we have to find this reference from 1920, and, if we can, go back to a primary source. Fortunately, Ellmann has left sufficient clues for us to solve the mystery.

Occam’s razor

From Ellmann’s text and footnote we know the story comes from a diary contemporary with the 1880s which was the subject of a newspaper article in 1920.

The first question I asked is why did we not know about the diary in the 1880s or 1890s? The simplest answer would be that a diary, being personal and often revelatory, might not have been published. But why, then, was the Evening News running article about it forty years later? Following the same logic: perhaps this was when it was published—and, perhaps, now that its author had died?

If so, we’re looking for a diary from the 1880s first published around 1920, containing the Wilde cello story, and with the suggestion to Ellmann of its being written anonymously (his reading of Secret Diary) by an author recently deceased. There surely can’t be many of those.

Voila!

In January 1921 there was such a publication in London: a journal of social life under the title Echoes of the ‘Eighties: Leaves from the diary of a Victorian Lady.8 An Editor’s note also confirms that the diary is anonymous, and was written “from 1879 through the ‘Eighties.”

The introduction by the editor, Wilfred Partington, unapologetically describes its contents as ‘gossip’—which he defended as being the more revealing stuff of history. And, indeed, the anecdotes betray an often playful, insider familiarity with London life and its literary celebrities, but no less believable for all that.

Included are stories about Thomas Carlyle, Henry James, John Everett Millais, John Ruskin, Algernon Swinburne, Alfred Tennyson, W. M. Thackeray, George Watts, and many more.

Much of the book consists of first-hand accounts such as the Lady’s meetings with Charles Brookfield or George Du Maurier; her conversations in society with Holman Hunt and Frederick Leighton; being called upon by Robert Browning; or being seated at a wedding service near “the Millais’ and the Blumenthals.'” Even second-hand reports are often attributed to friends who actually witnessed verifiable incidents, such as Queensberry’s disturbance of the Tennyson play The Promise of May, or who were present at events such as the death of Carlyle.

Admittedly many tales are unattributed, but this is done usually to protect a confidence, and it is a measure of veracity that the author never sought to publish the diary for profit, or otherwise.

A VIOL!

It is, of course, this mysterious Victorian lady who informs us about Oscar Wilde’s cello coat (p. 220-221).

Here it is: the first evidence of the Oscar Wilde cello coat story. Again, it is the 1921 publication of an 1880s diary:

What adds to the authenticity of the story is the suggestion that the Lady actually spoke to Wilde about it (“he can’t put a name to the ghost”). Moreover, the detail given about the coat’s material and seams, and how it looked in various light, implies that she actually saw the coat herself. Indeed, she records that Wilde wore the coat at a private viewing of the Grosvenor Gallery, which we know (p. 158) that she also attended. [This description of the coat is clearly replicated in Ellmann’s retelling.]

It is difficult to know whether Wilde actually had such a coat tailored. Given his penchant for fanciful tales, it is possible that his coat just happened to have the look of a cello, and the dream was just a story he spun for our diarist. This seems equally plausible as the cello coat was not remarked upon elsewhere at the time. I shall leave interpretation to artistic license.

Addendum: My further research suggests that Wilde did in fact have such a coat specially made, but that the event was not 1877..

See Cello Encore

Find the Lady

The diary itself would normally be enough for the verification of historical data, but it would lend credence the story, and complete the puzzle, if we could overcome the Lady’s anonymity.

We are fortunate that K. K. Collins in George Eliot: Interviews and Recollections, (Palgrave, 2010) has provided a starting point. That book indicated the name “Mary” by cross-referencing the diary with the same story told in the 1912 reminiscences of Scottish novelist and artist, Lucy B. Walford. However, although the name “Mary” is sound, that study could go no further in identification—and I explain the misreadings in its methodology in footnote.9

Cello Case Closed

One is grateful, however, for the research of K. K. Collins for citing the Walford memoir as a sourcebook, as it is replete with allusion to the missing diarist—many of her stories being either of Mary or gained from her.

So it is to Walford we look for more clues. This note in the introduction is initially useful in providing biographical hints:

This note tells us two things: first that Walford’s granting of anonymity to Mary means that she was probably still alive at that date (1912); and, second, that “Mary” was a name more informally used in society than otherwise—the suggestion being that she had a nom de plume that the name Mary would not obviously reveal.

So who was Mary?

My identification comes from conflating two pieces of internal evidence: one from the Lady’s diary and one from Walford’s memoir, as follows:

(i) In the diary: the Lady states (p. 121-122) that she attended the marriage ceremony of George Buckle, editor of the Times, and Miss Alice Payn, third daughter of Mr. James Payn, the novelist. It was a society wedding held at St. Saviour’s church in Warrington Crescent, Paddington. Newspapers recorded the notable guests fairly definitively as Lord Rosebery, Henry James, the Du Mauriers, Mr and Mrs Yates Thompson (proprietor of Pall Mall Gazette), Mr and Mrs Leslie Stephen (author, critic, parents of Virginia Woolf), Mr and Mrs Guthrie (comic writer Thomas Anstey Guthrie, aka F. Anstey), and Mr and Mrs Humphry Ward.10

It seems certain that as a noted lady of society our mysterious Mary must have been one of those listed.

However, when we refer to the same event in the Lady’s diary, one guest couple is conspicuously absent from her report. She names ALL of the guests listed above except for Mr and Mrs Humphry Ward. Could this exception have been made because our diarist wished to remain anonymous? Certainly, none of the other ladies listed was named Mary. Let us cross-check the attribution with another specific method of identification found in Walford.

(ii) In Walford’s memoir: on p. 67 after relating a story about the artists Sir John Everett Millais, Sir Edwin Landseer, and Henri Lehmann, Walford asserts, “Mary had her portrait painted by Lehmann shortly after this, and very, very good it was.”

This knowledge narrows down our search, because being the subject of a Lehmann painting would place Mary among a finite number of known sitters. A quick look at an old inventory Control record of the British Museum11 should confirm my suspicions.

Here we see our Mrs Humphry Ward confirmed among the list of prominent, mostly male, subjects of Henri Lehmann.

As a final confirmation, should it be necessary, we should now expect to find that:

* the given name of our diarist was Mary;

* she was a literary lioness of society;

* she adopted a pen name;

* and may have died in 1920 allowing the diary to be published.

If we inspect Mrs Humphry Ward’s biography we see those stars aligned.

Mrs Humphry Ward

Mary Augusta Ward CBE (1851—1920), was a British novelist who wrote under her married name as Mrs Humphry Ward.

As the niece of the poet Matthew Arnold, the grand-daughter Thomas Arnold (headmaster of Rugby School), the aunt of Aldous Huxley, and friend to dozens of Victorian era writers, she was steeped in the literary world. She wrote novels, children’s stories, articles for Macmillan’s Magazine, ten books of non-fiction, and, as we now know, a literary diary of the 1880s.

With such a pedigree, it is no surprise to learn that Mrs Humphry Ward is already known to scholars of Victorian fiction—although she does not prove too popular among Wildeans, for, despite being a pleasant and chatty diarist, she has a dour social reputation.

She was on the wrong side of history as founding president of the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League which campaigned against the vote for women. And in another act of clinging to Victorian values, she was also a prime mover in having Beardsley dismissed from The Yellow Book.

It appears that both she and her husband were too stuffy for Wilde and his circle. According to Harris, her husband Mr Humphry Ward, art critic of The Times, was the man, “filled with an undue sense of his own importance”, who sparked Whistler’s famous “you will, Oscar” riposte. And Oscar painted a critical portrait of Mrs HW in the The Decay of Lying when he characteristically quipped that Mrs Humphry Ward’s most famous novel, Robert Elsmere, was “simply Arnold’s Literature and Dogma with the literature left out.”

We ought to let Wilde have the final word. Again, from Harris:

“I don’t know why it is,” [Oscar] went on, “but I am always match-making when I think of English celebrities. I should so much like to have introduced Mrs. Humphry Ward blushing at eighteen or twenty to Swinburne, who would of course have bitten her neck in a furious kiss, and she would have run away and exposed him in court, or else have suffered agonies of mingled delight and shame in silence.”

Mrs Humphry Ward died in March, 1920; the Evening News article (Ellmann’s source) appeared in December 1920 prefacing the diary’s publication the following month.

© John Cooper, 2018.

See also addendum Cell Encore.

Footnotes:

- Oscar Wilde, Richard Ellmann, Alfred A. Knopf, 1987. Widely accepted to be as flawed in its accuracy of detail as it is admired for its power and style. The cello coat reference is on pp. 78-9. ↩︎

- “The Grosvenor Gallery” Dublin University Magazine, 90, July 1877, 118-26. ↩︎

- “Grosvenor Gallery” Irish Daily News, 5 May 1879, 5. ↩︎

- Cf. Cakes and Ale (1930), W. Somerset Maugham, ch. XIV:

“Are you going to send it to the Academy?

Good God, no! I might send it to the Grosvenor.” ↩︎ - A primary source here defined as the contemporaneous, documented, and reliable viewpoint of an individual participant or observer. Qv. my article Primary Sources. ↩︎

- Oscar Wilde at Oxford, by Richard Ellmann, Library of Congress, Washington, 1984, 9. ↩︎

- Additions and Corrections to Richard Ellmann’s ‘Oscar Wilde, 2nd Edition. Horst Schroeder, Braunschweig, privately published, 2002. ↩︎

- Echoes of the ‘Eighties: Leaves from the diary of a Victorian Lady, Eveleigh Nash Co. Ltd. (London), 1921. VIEW BOOK. The original diary is among the Ward family papers at UCVL Archives catalogued here. ↩︎

- Collins’ identification of the name “Mary”, and errata:

In George Eliot: Interviews and Recollections, (Palgrave, 2010) the author K.K. Collins included a recollection (p. 41) of George Eliot from the Lady’s diary. In a footnote he identified the diarist as an untraced “cousin” of Lucy Walford, by cross-referencing the same story in Walford’s own 1912 reminiscences. The story concerns a faux pas in the company of Eliot’s widow John Cross. It can be found in Echoes (p. 14) and in Walford’s Memories of Victorian London (Arnold, 1912, pp. 145-6).

There are two points to note:

(i) Collins draws upon Walford’s version of the story in which she says that “Mary” was the main protagonist of the Cross story. Whereas, “Mary” herself in the diary does not say she was present: she records the story with Mrs Ritchie at the center of the incident. However, the stories are told in such similar ways that the “Mary”, present or not, must be the source.

(ii) Collins’ assertion that Mary is a “cousin” of Lucy Walford is based on Walford’s own allusion to her as such, but the note concludes that she is “untraced”. This is probably because Walford did not have a cousin Mary.

Lucy B. Walford was the former Lucy Bethia Colquhoun, the youngest daughter of the son of Sir James Colquhoun of Colquhoun and Luss, 10th Baronet of the name. As such her relations are fairly well documented, and no cousin of Walford named Mary who lived beyond the 1850s has been found via her entry at thepeerage.com.

Rather, Walford’s use of the word “cousin” may refer to the claim of a distant cousin, or may simply be a term of kinship.

It may be more correct to take the Editor’s note in the lady’s diary itself, which describes Lucy Walford as “an esteemed friend of this entertaining diarist”, not a cousin. See extract below.

↩︎ - Yorkshire Gazette, January 24, 1885. Other guests were named including family members and unlikely candidates for identification. ↩︎

- , Volume 65. Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1907). ↩︎

This is some fantastic research! Color me impressed!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Superb sleuthing! You are the Sherlock Holmes of Wilde research.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’ve done it again Mr. Cooper! Perhaps “Mary” was just spinning yarns about Oscar’s new threads, to the likes of a Devil’s Trill. Thanks for your public service concerning this site.

LikeLike

Ah, but further research indicates a highly stylized coat did exist. See Cello Encore:

https://oscarwildeinamerica.blog/2018/01/16/cello-encore/

LikeLike

Dear Sir, Would you allow me to do a summery of your brillant article for “Rue des Beaux-Art”, the revue of the French Oscar Wilde Society ? I will mention your name, of course. Thanks a lot.

LikeLike

Je vous remercie, Guérin. Je répondrai par email. 🙂

LikeLike