Textual Analysis for Students

A verse parody appeared just three weeks after Oscar Wilde arrived in America. It was one many such newspaper items in 1882 that poked fun at Wilde and the aesthetic movement.

It was notable for its affected and satirical overuse of alliteration. Although Wilde was known for his occasional penchant for this verbal prose style (something that Whistler later parodied), it was probably not recognized by the author of this verse when it was written in January 1882.

It is more likely that its use was prompted by expressions such as “too-too” and “utterly utter” that were connected to the also alliterative Apostle of the Aesthetes.

As such, the text is instructional in understanding allusions to Wilde and the aesthetic movement. Let us examine the terminology:

GLOSSARY

Apostle

One who is sent away, often as a teacher or missionary to a people. Wilde’s stated mission was to educate the American people in art and culture.

Bard

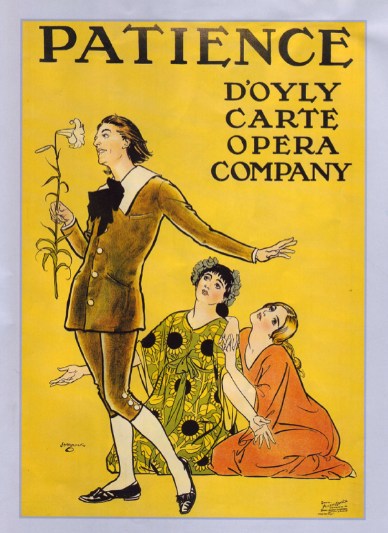

In medieval Gaelic and British culture, a professional poet, employed by a patron. Wilde’s patron was Richard D’Oyly Carte, promoter of Gilbert & Sullivan’s Patience, a comic opera which, like the verse, was a parody of the Aesthetic Movement.

China

Another name for porcelain, a ceramic material used in pottery. Wilde said, or it was said of him, that he was trying to live up to his blue china.

Esthetes

An alternative spelling of aesthetes, who were members of a movement that emphasized beauty as an artistic value. Wilde was known as a leader of the late nineteenth century Aesthetic Movement.

Fervid

Intensely enthusiastic or passionate, especially to an excessive degree, as Wilde was assumed to be about aesthetic art.

Gushing

Effusive or exaggeratedly enthusiastic.

Hifalutin

Overblown and pretentious; bombastic. Wilde was parodied as being all of these.

Intense

This word had a particular meaning as it related to Aesthetic Movement. British decadent writers were much influenced by the Oxford professor Walter Pater who stated that life had to be lived intensely, with an ideal of beauty. His text Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873), was a favorite of Wilde’s. The word came to be used satirically to mean the same as other words in the verse such as fervid, gushing, and hifalutin.

Jonquil

A bulbous flowering plant (or its color, yellow) of the species Narcissus. Narcissus was also a mythological character who fell in love with his own reflection, thus epitomizing beauty and vanity.

Johnny Bulls

John Bull is a personification of Great Britain, and England in particular, especially in political cartoons. He is usually depicted as a jolly, stout, middle-aged, country-dwelling man. Wilde was often referred to in America as English, but he was, in fact, Irish.

Knee-breeches

Trousers usually stopping just below the knee. They were worn for effect by Wilde while lecturing in America, and became a source of much ridicule, seen as anachronistic and pretentious.

Lily

Along with the sunflower, one of the floral emblems of the Aesthetic Movement. Wilde was fond of the word and became enamored of Lillie Langtry, often using the word in connection with her, although it was his male lover, Alfred Douglas, whom he called his ‘lily of lilies’ (Complete Letters, 651).

Medieval

The Aesthetic Movement grew from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood school of art whose prototypes harkened back to the simplistic styles of Medieval England (i.e. Pre-Raphael). Gilbert & Sullivan’s Patience, which parodies the Aesthetic Movement, contains the following lines with which Wilde became associated:

Though the Philistines may jostle, you will rank as an apostle in the high aesthetic band,

If you walk down Piccadilly with a poppy or a lily in your mediaeval hand.

Nature

Another allusion to the natural milieu of the Aesthetic Movement such as flowers, birds, peacock feathers &c.

Ornate

A reference to Wilde’s attention to the decorative arts.

Pure

The search for pure beauty in the Aesthetic Movement often led back to classical Greece.

Quixote

Alonso Quixano, The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha, from Miguel de Cervantes’ classic 17th century Spanish novel Don Quixote. His principal characteristic is eccentricity, his mental faculties having become distorted by excessive reading of books into a belief that the world is other than what it seems. Many thought Wilde to be under a similar delusion.

Queer

Although unintentionally prescient of its later use as a precursor of gay, the intended meaning is simply the traditional one of odd, strange or unusual.

Renaissance

A reference to Wilde’s first lecture in America, which he titled The English Renaissance, a title which harks back to Pater’s earlier study (see Intense above).

See web site for Wilde’s Lecture Titles.

Sunflower

Along with the lily, one of the floral emblems of the Aesthetic Movement.

Too-too/Utter

Linked to the cult of intensity and the contemplation of beauty, these and similar expressions poked fun at the refined attitudes of the school of art of arts’ sake.

Voluptuary

A person devoted to luxury and sensual pleasure.

White-souled

Innocent and pure.

Xorciser/Xecrable

The letter X used to foreshorten the words exorciser and execrable.

Yawper

To yawp is to talk noisily and foolishly; a reference to Wilde’s lecturing.

Yallery

Yellowy. The term ‘greenery-yallery’ became to be a parodic reference to the Aesthetic Movement); Gilbert & Sullivan’s Patience contains these lines:

A pallid and thin young man,

A haggard and lank young man,

A greenery-yallery, Grosvenor Gallery,*

Foot-in-the-grave young man!

* Wilde had written a review of the opening of London’s Grosvenor Gallery (Dublin University Magazine, July 1877). Related: Oscar Wilde’s Cello Coat.

Zealot

Person who is fanatical or uncompromising in pursuit of an ideal.

© John Cooper, 2018.

Dear John Cooper,

This is a wonderful post, an informative and succinct introduction to the 1890s. If you don’t mind, I’ll have my Victorian course students read it next month before we move into the 1890s.

Best, Linda Zatlin

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’d be honored. Thank you.

LikeLike

Today I made a list of all the roles Wilde played and came up with about thirty. He was encyclopedic.

LikeLike