John Cooper expands on comments he made as a member of a panel discussion at the Oscar Wilde Festival in Galway, Ireland, in 2014, in which he appraised Wilde’s legacy and his personal response to it.

(I) RISE AND FALL

Finding Oscar Wilde during his lecture tour of America in 1882 presented few difficulties. Throughout the year he made hundreds of appearances in public and thousands in the press. But his transatlantic sojourn was not merely prolific, it was a surprisingly formative time that saw Wildean firsts in all aspects of his career. Professionally, he nurtured the art of public speaking, began lecturing, and conducted his first press interviews. In his personal life he entered a new sphere of poets, writers, and statesmen; and he embarked upon a lifelong pattern of occasionally earning, but of always spending, large sums of money. Creatively, he became increasingly familiar with formulating his thought into thesis, while socially he was gathering material and honing epigrams for use in his early essays, short stories, and dramatic dialogues. Perhaps most surprisingly, it was in America that he staged the first ever production of a Wilde play.1 And lastingly, it was in New York City that the predominant image we have of him was formed with a series of photographs taken by Napoleon Sarony. After America, one might say, Oscar had become famous for more than just being famous.

Not surprisingly, given this degree of exposure and experience, contemporary opinion was that America had made a greater impression on Wilde than vice-versa. Supporting this view is the fact that his audiences, although they had attended his lectures, came to see rather than to hear him; and even though he was often personally liked, he was more often publicly ridiculed. Wilde’s maligned persona was so widespread that the ability to locate him in the abstract sense, even for those who had not seen him, also presented few difficulties. In sum: the breadth of his presence made Wilde familiar in person, and the stereotype of his character provided the measure of him as a personality.

We now see that Wilde cannot be so easily pigeon-holed.

Critical observers at the time knew that Oscar was no fool, and some rightly suspected him of manipulating the public for personal gain; but their suspicions remained just that, lacking, as they did, the context of history. Instead, it was the casual critique that prevailed: that of Wilde as a charlatan caricature. This view was persuasive because it contained a half-truth, the lie being that Wilde’s presentation of himself in 1882 was, in part, intentionally a caricature: a premeditated pose with America as voyeur to a form of exhibitionism. Finding the real Oscar was difficult enough, but if, as he later asserted, the truth is never simple, then his living a half-truth must have doubled the complexity.

The modern view is that Wilde’s aesthetic period was the preliminary phase of an ultimately ambiguous life. But such hindsight did not come easily. Discovering Oscar through his equally complex after-life was not only never simple, it was also, to complete his aphorism, rarely pure—not least to observers obsessed with personal morals and public morality. Indeed, morality was to remain the subtext to finding Oscar for over fifty years.

During this period, the surface debate about Wilde has ranged from public sanction to private squabble; from civil trials to changes in the criminal law. In print, too, there has been a wide and laboured forum. More books have been written about Wilde than any other writer in the last 100 years, while in academia there is a major variorum edition of his works in progress – currently a twenty-year undertaking. More popularly, there have been endless productions of his plays, myriad exhibitions and seminars. There are book stores and restaurants in his name. Even an opera.2 So how did we arrive at this peak of interest and analysis? And, did Wilde ever really go away?

(II) THE LATENT MUSE

There are many pathways to the modern Wilde. Perspectives range from the objective, typically with a literary interest, to the subjective, often based on an empathy with his lifestyle. In attempting to categorise my own relationship to Wilde I find neither a pathway nor a perspective, as both of these suggest an approach. In my case no approach was necessary. Mine was an entirely interior response, as if a spirit were in situ, waiting to be embodied. In reality, the spirit had been willing since I was exposed to the curriculum Wilde in high school, but any awakening in early adulthood would have to wait. The development of a temperament necessary for growth and appreciation of Wilde lay arrested by the attendant boorishness of a provincial town. Some years later, however, upon reaching London from the provinces and being granted a metropolitan freedom of thought, I rediscovered Wilde. In doing so, my nature found its personification: Wilde became the usher to an underlying sense of self that was academically sensitive to literature and the arts. It is hardly surprising for Wilde to be a champion by this process, as self-realization was an aim he preached and relocating to London was a path he chose.

In wondering why Wilde?3 the University of Connecticut professor Frederick Roden has pointed out that while many artists can be interpreted for the modern world, Oscar uniquely challenges us to be more ourselves. Much later, I learned that the painter, William Rothenstein, who knew Wilde, would have recognized this sense of burgeoning awareness. He said:

I had met no one who made me so aware of the possibilities latent in myself.4

This is a key observation, for it resonates with the process of latency and revelation that is so important in assessing how Wilde still has the ability to be an inspiration and influence. It is a phenomenon that extends beyond just the personal experience. By extrapolation, we also recognise a historically equivalent arc of discovery in society before Wilde became truly appreciated: a modern affinity for the depth of his life and work that emerged only after a long period of neglect.

(III) THE OSCAR WILDERNESS

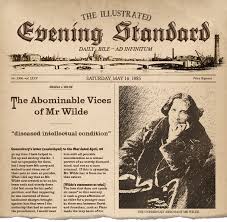

The opprobrium levelled at Wilde began immediately upon his imprisonment in 1895, and was so rife that it obscured the vision of the press and former associates too eager to condemn. After Wilde’s death in 1900 critics, too, became absorbed by his conduct at the expense of his works. There grew a bandwagon mentality that treated Wilde as a social pariah.

Against this, one person who attempted to reestablish Wilde’s reputation was Robert Ross, his former lover and literary executor, who successfully brought financial (and emotional) support to Wilde’s sons by restoring the family rights to the Wilde canon. This was important because the production of his plays did not cease, and in that sense Wilde the entertainer has never left us.

But in the early years of the century, any personal sympathy that Wilde might have received was stifled in public discourse by what Vyvyan Holland, called ‘a conspiracy of silence’. Commentators spitefully made it fashionable for him to be consigned to history as a minor literary figure, to be grouped along with other fin de siècle decadents in his circle such as Ernest Dowson, Lionel Johnson, and Richard Le Gallienne. Particularly inexcusable was Wilde’s closest friend and lover, Alfred Douglas, who selfishly squandered his unique position to be an advocate for Wilde with a notorious volte-face under oath of his character and his value as an artist: he declaimed Wilde as ‘the greatest force for evil that has appeared in Europe during the last three hundred and fifty years,’ adding that Wilde’s Salome was ‘a most pernicious and abominable piece of work’.5 Even Wilde’s biographers, whom one might have expected to be forthright or fair, produced formula accounts, occasionally fanciful, but usually afraid or unable to delve beneath the level of personal reminiscence. When they did express an opinion it was often equivocal, with objectivity marred at one end of the scale by fanaticism, or, at the other end, by justification. There were those who were obliged to be reasonable, such as encyclopedia editors, but even they grudgingly recognised only one or two of Wilde’s works as having merit. They lacked, like many others, the generosity to read his work sympathetically, and the vision to appreciate any inherent philosophy.

The constituents of the connivance against Wilde were:

- the maligning of his intellectual reputation,

- the misunderstanding of his personality, and, latterly

- the failure to recognize the stature he commanded as a modernist.

The result was that society, particularly polite society, knew Wilde the writer only as a wit, and Oscar the man not at all. People saw only lightness in the body of his work; and only darkness in the soul of his life.

(IV) BODY AND SOUL

The spirit of the age had no Wildean sympathy and for years the spectre of those who had crossed the street to avoid Oscar in his exile haunted his rehabilitation. In particular, a significant skeleton that remained closeted was Wilde’s philosophy of identifying the soul as counterpoint to the body or the senses.6 Today this would be fertile ground for interpreting his character and his motives.

But in the first half of the twentieth century, analysis of Wilde’s literature and lifestyle was barren of sensibility and sensuality. How could people see if it was taboo to read; how could people feel if it was illegal to touch? It would take decades to arouse the legitimacy of a soul inherent in Wilde’s literature, and still more years to legitimise the arousal of a body inhabited by Wilde’s lifestyle.

Yet the ignorance that underpinned the neglect of Wilde was not always willful. It should be remembered that portions of Wilde’s long letter De Profundis, in which he explained (without excusing) himself, had been suppressed, and most of the other letters or personal testimony that reveal Wilde as a compassionate figure, had not yet surfaced. It took until the 1950s before both Wilde’s literature and lifestyle began to be reappraised.

(V) LABOUR AND TOIL

The impasse in finding Wilde started to give way to serious analysis, most strikingly in George Woodcock’s acute The Paradox of Oscar Wilde (1949) in which, as the author said, he was ‘considering Wilde as a thinker and as a writer of didactic tendencies rather than as a social lion or a voluptuary.’ Nevertheless, an author such as St. John Ervine could still publish a bitter ad hominem attack of Wilde and his type.7 This concept of the ‘Wilde type’ – obviously as effeminate – was a significant epithet in the 1950s that was gradually weakened into cliché by its longevity to become the final barrier to Wilde’s restoration. Homosexuality began to emerge from subtext into subject.

In Britain, the groundswell of public opinion toward acceptance probably began in 1954 with a confluence of events that included the fallout from the landmark Montagu case8 and the suicide of Alan Turing.9 That same year, Vyvyan Holland, who had once found it necessary to conceal his birth name and identity10, proudly announced both in the title of his touching memoir Son of Oscar Wilde. In the book, Vyvyan recalled that his brother, Cyril (who had been killed in the Great War) had become a soldier partly to overcome what Vyvyan described as his ‘tragic youth’ filled with a ‘weight of knowledge [about his father] that he was too young to bear’. In describing how Cyril had faced this continuing struggle, Vyvyan quoted a letter Cyril had written to him from an army outpost in 1914:

I must be a man. There was to be no cry of decadent artist, of effeminate aesthete, of weak-kneed degenerate. That is the first step. For that I have laboured; for that I have toiled.

This plea is extremely useful in informing how Vyvyan Holland was better placed than most to appreciate the polemics of the effeminate decadent. On the one hand, his father had infamously died embracing the taint, while on the other, his brother had valiantly died determined to distance himself from it.

Vyvyan claimed that he had cited his brother’s words to ‘show how iron had entered [Cyril’s] soul,’ and Vyvyan’s purpose may well have been solely biographical. But in 1954 there were 1,069 men in England and Wales in prison for homosexual acts11 and legions of others who had also labored and toiled but with an increasing awareness that mettle could no longer assuage aestheticism, weak-kneed or otherwise. By writing the book at this time, and by quoting his brother in this way, it is intriguing to wonder whether Vyvyan also intended to illustrate the contemporary pathos and futility of forty year-old attitudes. Either way, those close to change in the current climate must have realised that they stood at the tipping point in a cultural reappraisal of masculinity.

(VI) THE LAW IS AN ASS

The force that eventually swayed the balance in attitude was attrition. By the late 1950s, most of those who knew Wilde had died, and their agenda was dying with them. Sympathy and tolerance fueled the call for a change in the law that had convicted Wilde, Montagu, Turing, and thousands of others. In 1957 the Wolfenden report12 recommended just that. However, there was no immediate legal effect from Wolfenden, and, were it not for the action of pressure groups, the report may have gathered dust. Oscar, however, now that he had started to come back to us, would not be left on the shelf.

A good example of the popular shift around this time is that Wilde, still too controversial, had never been portrayed as a character on screen. He made his first obscure appearance in a Canadian drama series in 1955.13 Then, significantly post-Wolfenden, he could be found in episodes of two separate UK and American TV series in 1958,14 and he was also the subject of two biographical feature films that were put into production, both of which were released in 1960.15

It took until 1967 for the Wolfenden recommendations to be enacted, but the continuing political debate kept Wilde in the spotlight as the preeminent victim, not only of outdated Victorian values, but of the very law from 1885 that was about to be repealed.16 Lord Arran, who three times sponsored the bill through the Lords that decriminalized homosexual acts between consenting adult males in private, quoted Wilde on the day the law was passed; he said in the House:

Mr Wilde was right: the road has been long and the martyrdoms many, monstrous and bloody. Today, please God! sees the end of that road.

For the millions who had been forced to live veiled lives, and this includes the sensitive heterosexual, it is appropriate that Wilde was invoked that day as the touchstone for exposing homosexual bullying and bigotry. In The Decay Of Lying, Wilde posited that art was not a mirror to life, it was a veil through which we see it. But it is also true of Wilde that personality was a veil to lifestyle. So it is ironic, and fittingly inverted, that when the English judicial system denied Wilde that veil, it revealed a personality that was to become a mirror in which the law would see reflected its own face of prejudice.

(VII) BEYOND RECOGNITION

As same-sex issues achieved acceptability, Oscar was destined to be perceived more sympathetically; what was needed was someone to augment the shift in sentiment with a renewal of literary respectability. This appeared most prominently with Richard Ellmann’s monumental, and richly flawed, 1987 biography Oscar Wilde – which added a scholarly deference to Wilde, and became one of the best-selling literary biographies of all time. Add to this the release of hundreds more examples of Wilde’s correspondence in the Complete Letters (1999) plus the discovery of his trial transcripts, and a greater understanding of Wilde was being fostered. A consensus seemed to emerge that Wilde had not only been cruelly treated, but also that he had been unfulfilled at the very moment he verged on greatness. It was as if modern audiences wanted to make amends for history.

The postmodern Wilde probably begins when Ellmann, in his preface, recognized Oscar as ‘one of us’.

It had long been accepted that Wilde was avant-garde in the literal sense of ‘forward looking’ – notably in the areas of lifestyle choices, women’s issues, prison reform, and, as I have expanded on recently, dress reform.17 Even his dilettante socialism incorporated the antithetical, but progressive, idea of personal growth.18 But the view now was that Wilde was more than just prescient; he was effectively the midwife to modernity.

Such a view suggests that Wilde transcends mere new age relevance: he was in fact the proto-modernist. Several facets of Wilde’s life and work inform this idea. First is the notion that Wilde almost single-handedly invented the cult of celebrity before it even existed. Other pretenders to this claim, such as Byron who predate Wilde, are historically isolated. Wilde, however, stands at the beginning of a continuum of modern era celebrities. He anticipated the techniques of projecting an image, self-promotion, making an entrance, being controversial, and being different, ideas which are still being explored.19 Another consideration is that Wilde’s modes of behavior were ahead of their time. His playful irony and disregard for the truth in favor of an epigram (the latter-day sound bite) were attitudes taken as shallow or vulgar in Victorian times. But today, the acts of flouting convention and flaunting pretension are acceptable to audiences who take themselves less seriously. Wilde was so far ahead of his time that he tempts us to speculate, even to understand, how a modern man might fare if parachuted into 1890s, and this also helps to explain his continuing popularity. Finally, and the most progressive aspect of Wilde’s modernity, concerns his works. There is now a sense that in addition to the sparkling wit contained in the words on the page, there is as much to be read into Wilde’s philosophy between the lines. Consequently, we now find the complexity and ambiguity of Wildean thought informing interdisciplinary study in academic circles.

Such is the scope of Wilde’s literary appreciation that it prompts one to reevaluate his rueful remark that he had put only his talent in his works (and his genius into his life).20 Some years ago on a radio talk show,21 a distinguished panel of Wilde scholars attempted to explain to a challenging host how Wilde had actually achieved this. But the panel never really resolved the question to the skeptical host’s satisfaction. I suggest the struggle to do so lay in their taking Wilde at face value. It is probable that the remark about his genius and talent was not literally true. It may have seemed that way because the balance between his life and work was always tenuous. But consider the reverse. I suspect his perfect conversation and cultured persona had elements of careful rehearsal; in that sense, achieving a veneer of genius in his life was, in fact, Wilde’s talent. More probably, his regret was not that he failed to put the genius of his personality into his works, but that he was compelled to do so covertly. He can be found in Bunbury, in Dorian, and in Lord Henry; he is part Willie Hughes and part Arthur Savile; indeed, Wilde is in every character he invented who had a secret. So the solution, which would not be Wildean if it were not paradoxical, seems to be that Wilde’s life is in his works, and by extension so is his genius. By creating this duplicity, Wilde anticipated his own prediction of a modern psychology that we live ‘more lives than one’; and by living his life in tandem with his characters, he exemplified it.

So today it is possible to find Oscar. This concept of the other life, often a subjugated one, is useful in the pursuit, and this is true whether we wish to locate him for ourselves (and Wilde is often appropriated), or to place him at large.

For those, like myself, born before the Wilde enlightenment, finding him for oneself meant dealing with the vestiges of fear and ignorance. Any Wildean susceptibility to nuance, delicacy, or art, required daring in the face of ridicule. A rapport with Wilde had to emerge as a discovery from within. Thus, one might say, that despite my disposition too long repressed, Wilde has come to represent the possibilities latent in one.

In finding Wilde at large, too, the deferred muse is also evident. But unlike the immediacy of a personal transformation, the wider world had to wait for changes in the law and for a cultural shift before a critical mass could catch up to Wilde. His eventual emergence came only after an epic hangover that took almost a century to wear off. Thankfully, it is now easy, one might dare to say natural, for scholars to locate him in subjects as varied as queer theory, gothic fiction, performance and gender issues, and critical studies. We now discern Wilde not just as a quotable wit, but as a thinker and a moralist, a man possessed of insight into the relation of art and life. Thus one might conclude that despite his reputation too long suppressed, Wilde has come to represent the possibilities latent in society.

© John Cooper, 2015

First Published in The Wildean (the journal of the Oscar Wilde Society, London).

Notes

- Vera; or, The Nihilists opened at the Union Square Theatre, New York City, on 20 August, 1883.

- Oscar, an American opera in two acts, with music by composer Theodore Morrison and a libretto by Morrison and English opera director John Cox. It received its world premiere at The Santa Fe Opera on 27 July 2013. Opera Philadelphia first presented a revised version of the opera on 6 February 2015 (my review).

- Palgrave Advances in Oscar Wilde Studies, (Introduction p.1), 2004, Frederick S. Roden, ed.

- Men And Memories, A History of Arts 1872-1922, Being the Recollections of William Rothenstein, Tudor Publishing Company, New York (1930), p. 87.

- At the trial of Noel Pemberton Billing MP for criminal libel, Old Bailey, May 1918.

- The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), Ch. II.

- Oscar Wilde: A Present Time Appraisal St. John Greer Ervine, G. Allen & Unwin (1951).

- Lord Montagu of Beaulieu (b. 1926) was imprisoned, for twelve months for ‘consensual homosexual offences’ along with Michael Pitt-Rivers and Peter Wildeblood, under the same law that convicted Wilde.

- Alan Mathison Turing, OBE, FRS (1912-1954) mathe-matician, pioneering computer scientist, and cryptanalyst at Bletchley Park, Britain’s codebreaking centre. Pleaded guilty in 1952 to a charge of gross indecency, and underwent hormonal treatment in lieu of imprisonment. Committed suicide 7 June 1954 (cyanide poisoning). Posthumous royal pardon, 2014.

- One example of several from Son of Oscar Wilde is the story Vyvyan told school friends at Stonyhurst that his father had been an explorer lost at sea (p. 132).

- Patrick Higgins, Heterosexual Dictatorship: Male Homosexuality in Postwar Britain, London: Fourth Estate (1996).

- The Report of the Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution, (1957). Lord Wolfenden, chairman of the committee.

- In Canada Wilde was played by actor John Harding in The Return of Don Juan, an episode of ‘CBC Summer Theatre’.

- (i) In the US Wilde was played by Australian actor John O’Malley in The Ballad of Oscar Wilde, an episode of ‘Have Gun-Will Travel’. (ii) In the UK Wilde was played by Welsh actor Paul Whitsun-Jones in Death of Satan, an episode of ‘Armchair Theatre’ (Season 2, Episode 37), a reprise of the CBC Summer Theatre play (see 13) under a different name

- The Trials of Oscar Wilde (Peter Finch) and Oscar Wilde (Robert Morley).

- The Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, repealed by Sexual Offences Act 1967.

- John Cooper, Oscar Wilde on Dress, CSM Press (2013)

- The Soul of Man under Socialism (1891).

- e.g. David Friedman, Wilde in America, Oscar Wilde and the Invention of Modern Celebrity New York: W.W. Norton (2014).

- ‘J’ai mis tout mon génie dans ma vie; je n’ai mis que mon talent dans mes œuvres’. (I put all my genius into my life; I put only my talent into my works). Conversation with André Gide in Algiers, quoted in a letter by Gide to his mother (January 30, 1895) and subsequently quoted in Gide’s work and recalled in his journal.

- In Oscar Wilde, an episode of the BBC Radio 4 programme ‘In Our Time’ hosted by Melvyn Bragg. First broadcast December 6, 2001. Available at: www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00547m3

Exceptional insight on your part John. And how fickle of society’s congregation as to being unable to rise to the occasion of his death, by at least reciprocating some measure his own fearless ability to present – lest they represent.

LikeLike

Wow, thanks, John. Great final paragraph. And the bit about living more lives than one is well-placed. I shall have to read it again. Now, what about Wilde and Shaw – Shaw was also promoting new world views, nein?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Don’t know much about Shaw—not sure if that’s a triumph of focus or a focus of failure.

LikeLike

I loved this piece of writing with its scholarship and touches of personal insight. It is hard to read Wilde without thinking of Wilde the man. In the theatre it is another matter: the plays carry you along. Your points about characters’ secret lives are interesting. I shall think about them when I go back to the texts.

LikeLiked by 1 person