Philadelphia Library Acquires Rare Typescript of “De Profundis”

On a balmy Sunday lunchtime last Spring I found myself in the refreshment area of the prestigious New York Antiquarian Book Fair. The ambience and the food were very pleasant, which should have been a portent of the standards I was about to discover, had I not been obliviously more concerned with fitting in,

My café table had an inlaid chessboard and what alerted to me to how I fitted in was made clear in an early gambit. The kindly stranger opposite made the first move. “Are you a dealer or a collector?” he asked, with an air of inevitability that suggested a third alternative did not exist. As I was such a third alternative I decided to counter with the department store maneuver: “I’m just browsing.” It was a defense designed to replace the probability of being actually neither with the possibility of vaguely being either.

However, it soon became apparent to me, if not to my new friend, that even the self-imposed rank of ‘browser‘ wildly overstated my standing as a potential customer.

The epiphany came in the form of a Romanesque book which happened to be laying on the table in front of me. There was I thinking how well met the European coffee and I were with this hardback Italianate volume when I realized it was not the collectible I thought it might have been. This handsome artifact was, in fact, merely the catalogue for the actual books on sale. And the prices therein defined for me the pathos that exists between browsing and simply gawking.

So I amused myself for a while.

Sir Francis Bacon’s 1620 Novum Organum seemed a bit over-egged at $25,000 and for me a little hard to swallow no matter how skillfully “the calf had been rebacked and recornered”; $100,000 for an “eyewitness” account of the Lincoln assassination required thinking outside the box as it was evidently written by someone who had only overheard it. Ansel Adams prints of the Yosemite Valley were predictably steep, and there was a Gray’s Anatomy that cost an arm and a leg; I was attracted by a fine example of the cartographer’s art dating from about 220 BG (Before GoogleMaps) of the western parts of Virginia, but you’d think for $150,000 you would get the whole state; and I wondered whether a rare Shakespear (sic) Third Folio priced at a voluminous $500,000 would be any cheaper in a handier size.

You will appreciate from such observations that, having already disqualified myself as dealer, collector and browser, I now also failed miserably as a serious gawker. In reality I was simply a curious visitor, and, as my area of curiosity is Oscar Wilde, I wandered over to a noted UK dealer of Wildeana who showed me something very curious indeed. Following the chatty preliminaries, he handed me a sheaf of typewritten papers bound at the corner. “Take a look at this,” he said.

I Blame My Shelf Terribly

A brief examination was all that was required to know that the half-decent Oscar collection in my small library at home had not prepared me for what I now held in my amateur grasp of serious collecting.

What I had was a typescript of the originally unpublished portions of Wilde’s passive-aggressive prison masterpiece De Profundis prepared by his literary executor, Robert Ross. Remarkable enough you might think, but that was only half the curiosity—for which typescript was this?

It was not one of the two original typescripts (or typescript and carbon copy) that Oscar asked Ross to have made after his release from gaol, because both of those are lost.

Nor was it one of the three extant typescripts Ross also made, probably for private circulation, which are housed in the Clark Library (of course). At least not unless this dealer had raided the Library vaults during its recent refurbishment.

Nor, again, was it the one identified by the Oxford University Press Complete Works as the British Library Typescript: BLT-S, a designation that would warrant more cryptic comment had I not already mentioned Bacon.

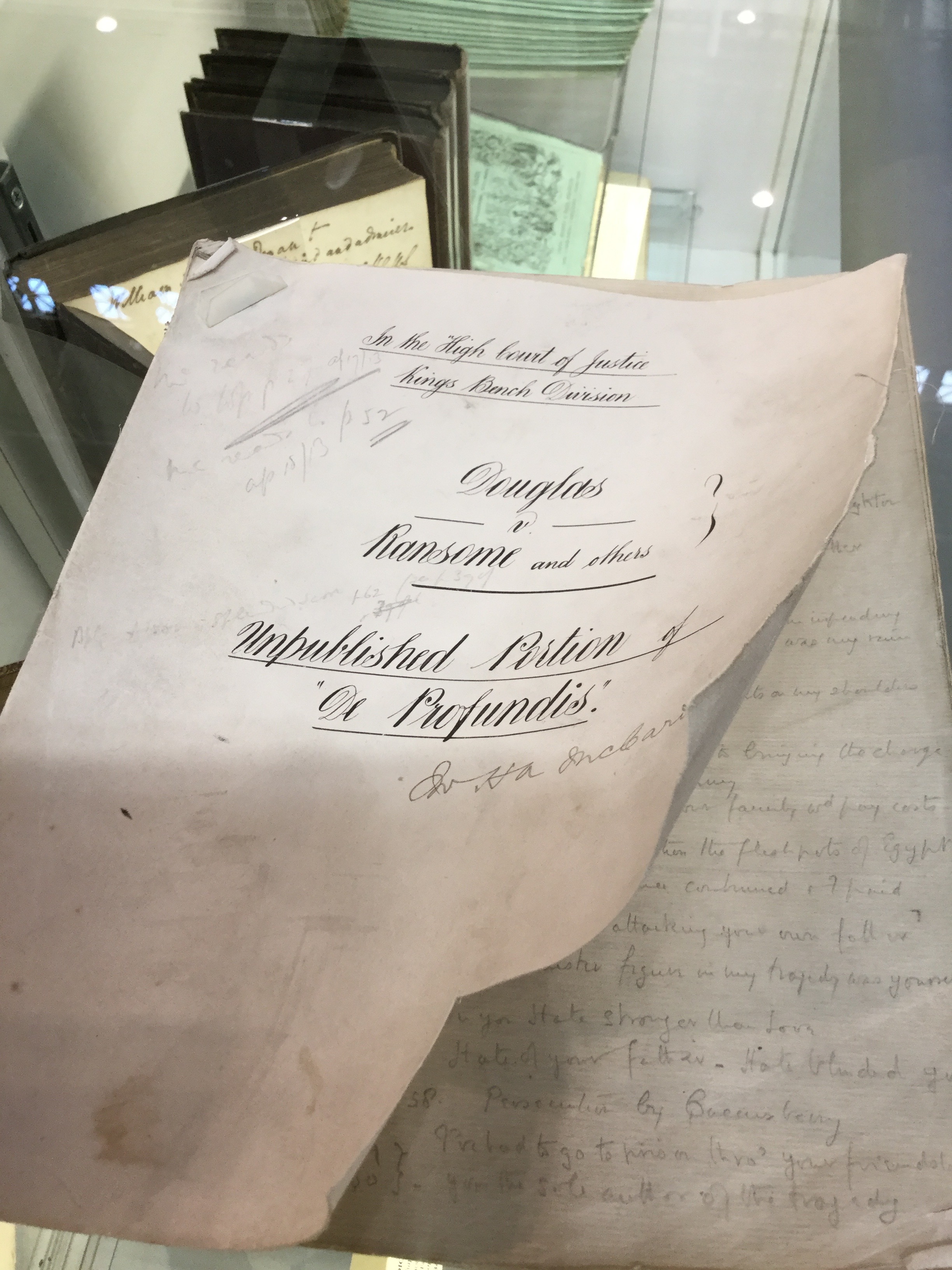

Fortunately the document came with its own provenance in the form of an attached cover sheet which reads:

“IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE

KING’S BENCH DIVISION

DOUGLAS V RANSOME AND OTHERS*

UNPUBLISHED PORTION OF “DE PROFUNDIS”

[* The Times Book Club.]

From the cover we can infer that the TS was prepared at the time of the 1913 trial when Lord Alfred Douglas (Oscar’s lover Bosie) sued a young Arthur Ransome for having the temerity to imply in his 1912 book on Wilde A Critical Study, that a person he did not even name might have had something to do with Wilde’s downfall. Even such a veiled reference was enough for Douglas to take legal umbrage,

Ransome won the case, however, because he was ably (and financially) supported by Robbie Ross, whose coup de grâce was to dig up the original manuscript of De Profundis from where he had interred at the British Library.

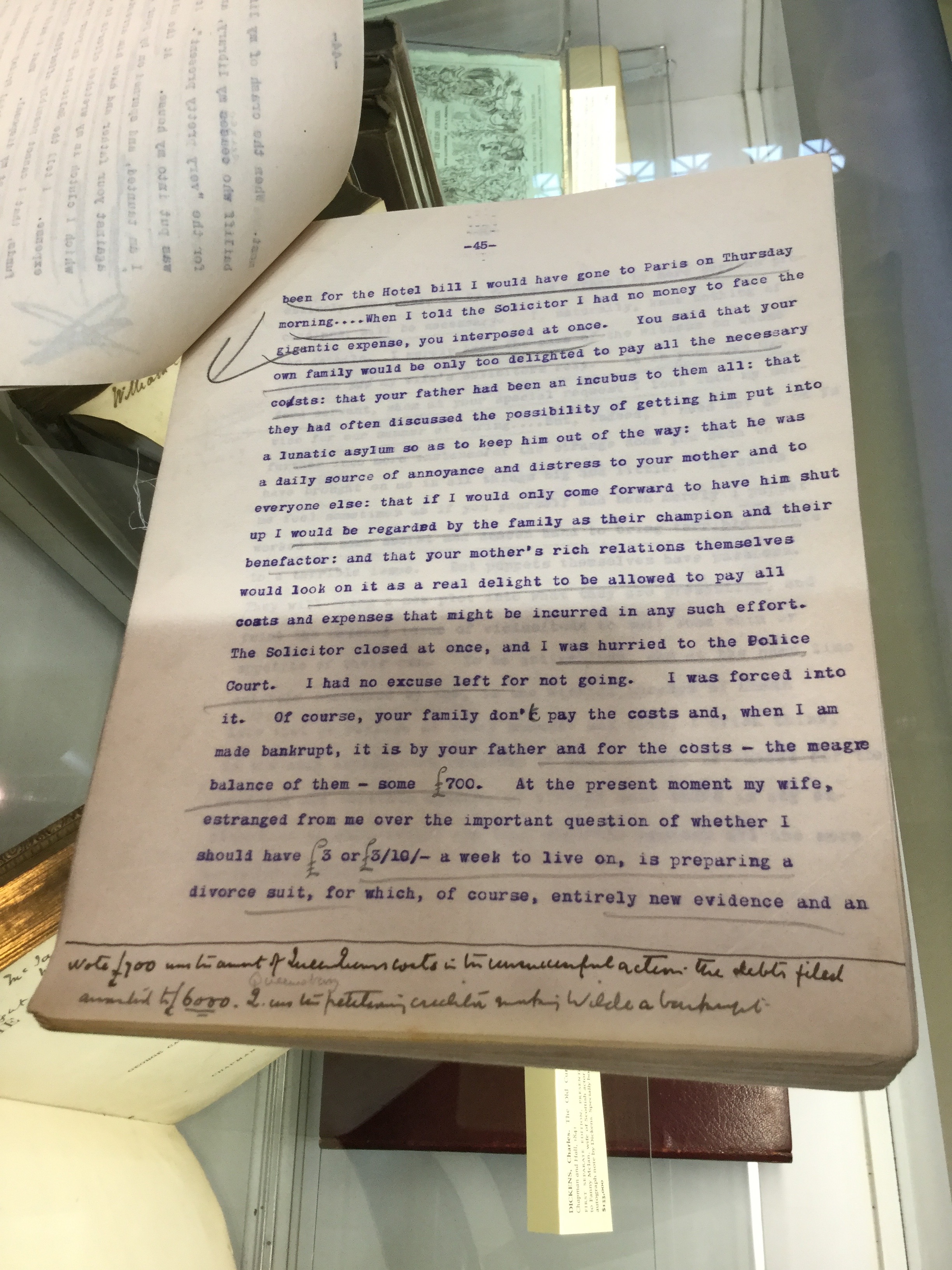

And it was from that original that the present typescript was prepared for use by Ransome’s counsel during the trial, now highlighting the previously expurgated portions of the text in the 1905 edition that were damaging to Douglas. The revelations came as a surprise to Bosie because back in 1897 he had probably thrown his copy, if he received a copy at all, on the back of the fire reading no further, I would suggest, than Wilde’s words “loathing” and “contempt” on the first page.

For Bosie now to hear home truths about himself and his relationship with Wilde in open court for the first time, sixteen years after previously ignoring them was a Shakespearean event. I was half tempted to dash back to that Third Folio with a red Sharpie to underscore the words hoist and petard which Shakespeare might have coined for this very moment. Fortunately for bibliophiles of the Bard everywhere, I was still shy of the half a million dollars required to procure it.

Meanwhile back in court, Bosie, no mean Shakespeare scholar himself, would have recognized how tragedy turned to tragicomedy when his counsel, Mr. Hayes, likened the tactic of unearthing De Profundis to mummies being subpoeaned from the British Museum in order to give evidence. When the defendant’s counsel disparaged this allusion, Hayes retorted, to laughter from the court, “don’t speak disrespectfully of mummies. You may be one yourself one day.” Not to be outdone, Mr. Justice Darling, presiding, struck a further historical note by ruling that it was not possible to libel the perversions of the dead, speculating that, “if you could what would become of old Caligula?”

Such was the mood of the trial which also included much impertinence from our litigious Lord AD who was continually rebuked by the judge for his attitude, and for initially being absent when Wilde’s damning letter was being read out. Who can blame him?

Letter of Credit

More seriously, and more to Bosie’s credit, one interesting snippet emerged from the trial.

On the euphemistic subject of “vice,” Douglas was cross-examined about the content of his letters. I quote from one he had sent at the time of Wilde’s imprisonment as it seems to be little known. Douglas wrote to Ross:

“If Oscar Wilde only loves me half as much as I love him—if he comes out of prison nothing in the world will keep us apart. All friends and relations, all their plots and all their plans will go to the winds once I am alone with him again and am holding his hand.”

Museum Quality

Finally, let us return to the typescript.

As a document used by the King’s Bench in the Ransome case, a King’s ransom was naturally the price tag. Again, the means escaped me. So I left the item to posterity demurring to the encouraging news that an American institution had already expressed an interest in it.

And so it came to pass. Last week I learned that the typescript has been acquired by the Rare Book Department of my local Free Library of Philadelphia, meaning that I can have the thing near me after all without having to buy it.

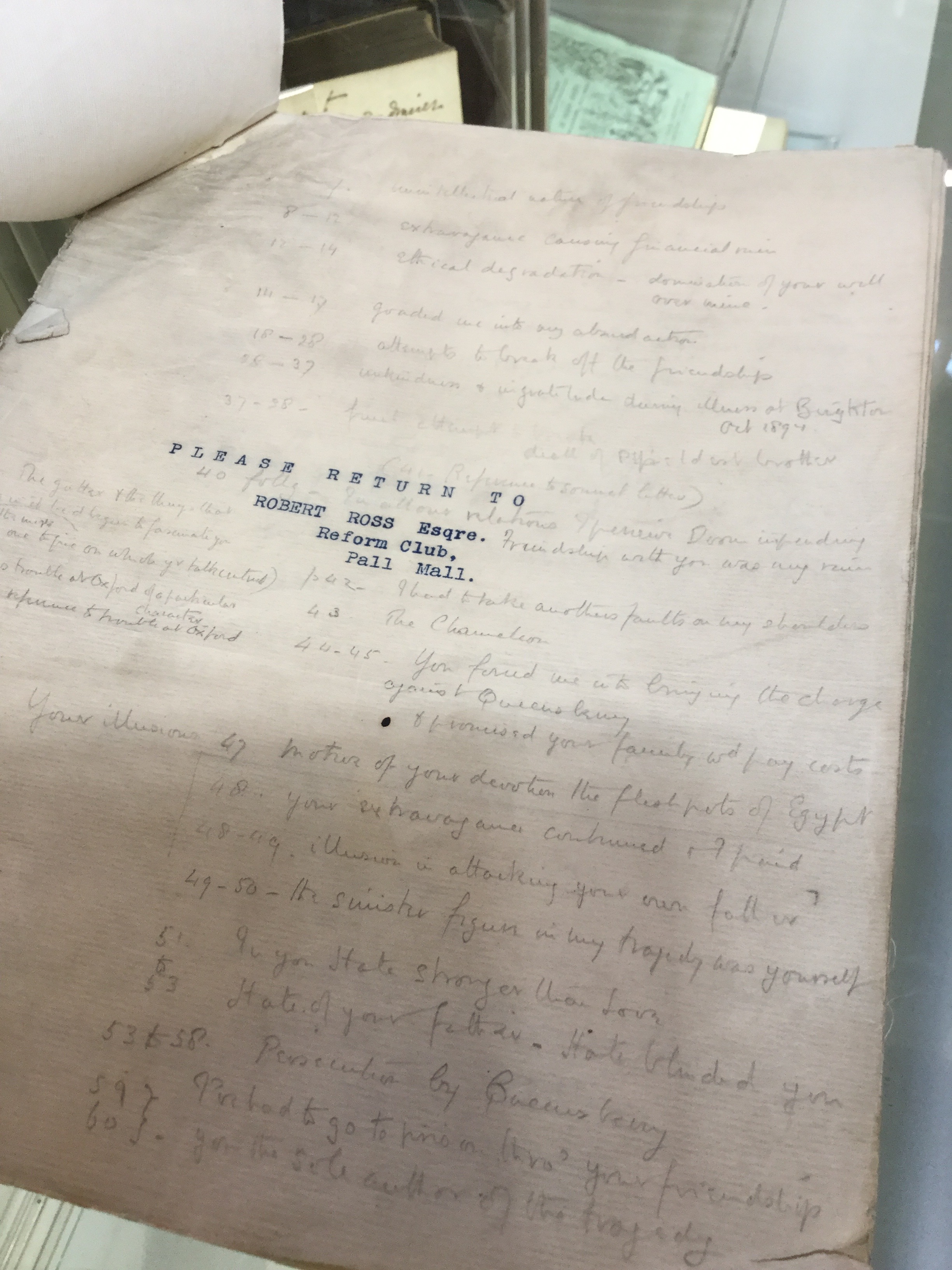

For those more remote from Philadelphia it has been incorporated into the literary manuscripts collection and is available online. It is worth checking out, if only to view the marginalia which includes case notes and a revealing footnote by Ross (suspiciously) exaggerating Wilde’s bankruptcy losses—but that’s another story.

© John Cooper, 2016. Updated 2023.

I assume that tomorrow’s jury will forever be out, on this matter – being that the dead – forever unable to truly defend themselves – appreciate your pursuits. As I do your articles. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for including photos. My hands shake at the thought of being near a humble typescript. I wouldn’t survive an original manuscript.

LikeLiked by 1 person